My research led me to discover Elizabeth Billington, who was performing in Naples in 1794—at the same time of a volcanic eruption—and that coincidence led some to suggest the natural disaster was a sign of heavenly displeasure with her. Yet, she was well-known enough to have been the subject of a James Gillray caricature, and possibly talented enough to have received three minutes of applause.

Opera wasn’t only for the upper classes during the time of Mrs. Billington, but was entertainment for the masses. When one opera venue discontinued its sale of half-price tickets, a riot erupted and the discounted prices were reinstated.

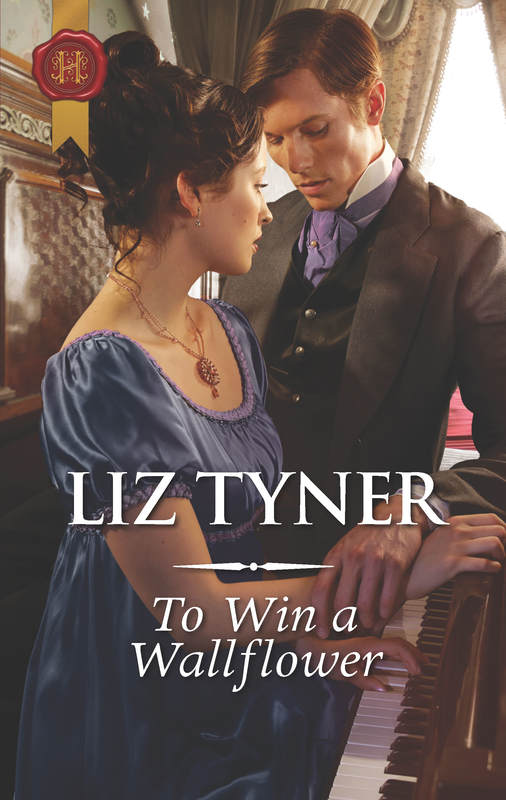

The performances had the entertainment value of going to a movie today, only with the added attraction of socializing. The houses were lighted enough for people to play cards during a performance. If the action onstage didn’t keep the spectators attention, it was acceptable for them to converse, much like dinner theater todady.

And many of the composers heard in the 19th century are familiar names for modern opera lovers.

My heroine, Isabel, would have been twenty-four years old when Rossini’s Barber of Seville was first performed in London, and based on her interests, she would have been in the audience during at least one of the performances, if not for several of them. In 1814, one year after Isabel married, Mrs. Billington’s last performance would have been at Whitehall Chapel, and Isabel would have applauded her, maybe even for the full three minutes.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed